Duo Spotlight: Laurel & Hardy

Life is full of dynamic duos–two halves from opposite ends of the spectrum colliding at just the right moment, and instantly creating iconic perfection. It gets to the point where you can’t have one without the other. In similar fashion, it is hard to imagine Mr. Laurel without the jovial (although often frustrated) Mr. Hardy.

While Laurel and Hardy are known as a pivotal comedic duo today, their professional partnership was prefaced by their two very different lives that started far from Hollywood. Stanley Laurel or Arthur Stanley Jefferson was born in 1890 in Ulverston, England, while Norvell Hardy was born in 1892 in the small town of Harlem, Georgia.

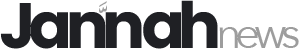

Laurel was born on June 16, 1890, on Argyle Street in Ulverston, England. His parents worked in the theater, often traveling, leading Laurel to be mostly raised by his maternal grandmother while also attending school. His family moved to Glasgow, Scotland, where his father managed the Metropole Theatre. Laurel began to work there developed an interest in performance, making his stage debut at Glasgow’s Panopticon at age 16. There, he gained experience as a comic, finessed his trademark nonsensical understatements, and became attached to his iconic bowler hat.

In the years to follow, Laurel spent time in the comedy double act, The Barto Bros., touring various countries. He would later join Fred Karno’s troupe of actors, which also happened to include a young Charlie Chaplin, whom Laurel would understudy. After his work in Karno’s troupe, Laurel continued working on the stage until eventually transitioning into working in films.

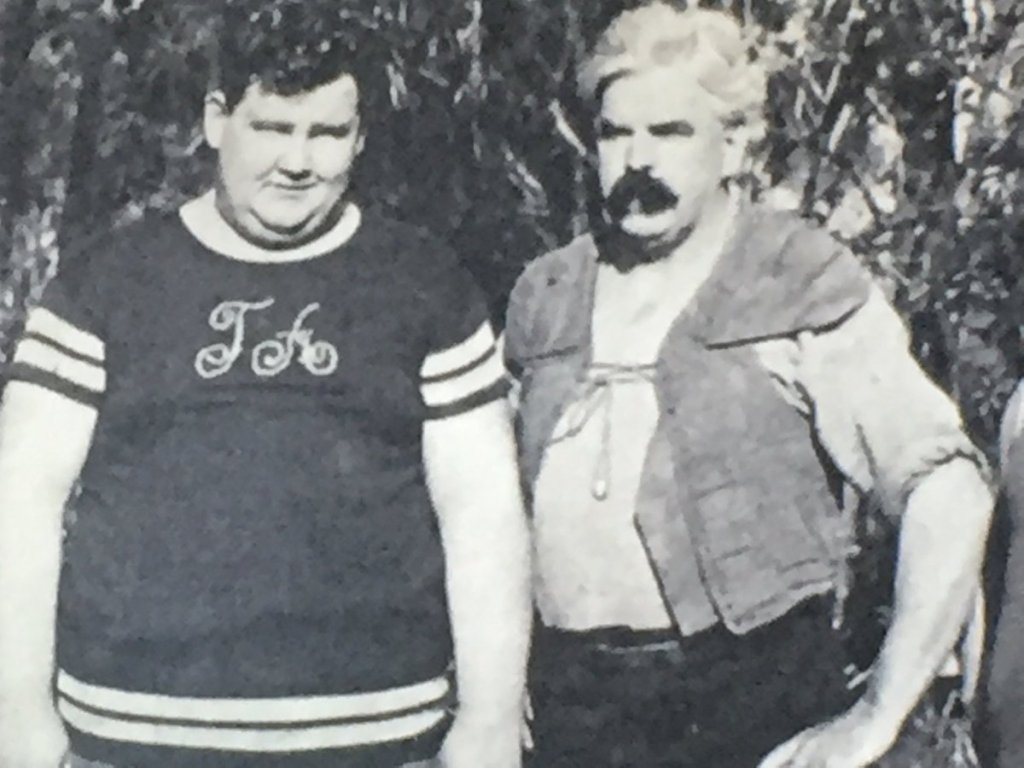

Norvell was born to Oliver Hardy and Emily Norvell on January 18, 1892. His father was a Confederate soldier and later became a tax collector upon being injured at the Battle of Antietam. Though the Hardys moved to Madison, Georgia, just before Norvell’s birth, Emily continued to own a house in Harlem that she rented to tenant farmers. Oliver died just one year after Norvell’s birth, leaving baby Norvell to be raised by Emily.

Growing up, Hardy’s life was full of ups and downs. Norvell was the youngest of five Hardy children. Unfortunately, tragedy struck when his brother, Sam, drowned in the Oconsee River. Hardy pulled Sam out of the water but was unable to revive him. Despite this family trauma, Hardy’s mother continued to occupy herself with keeping up the Harlem home and raising her family. Although she housed a varied of tenants, the people that she housed most often possessed a passion for music and theater.

Though Hardy attended schools such as Georgia Military College and Young Harris College, his interest in education was minimal. Instead, the vigor and glee of his mother’s tenants no doubt amused young Hardy, and soon enough, he headed for the stage. Hardy ran away from his boarding school in order to sing with an Atlanta-based theatrical group.

When Hardy’s mother learned of his affinity for performance, she supported his talents and paid for his lessons in music and voice. In memory of his father, Hardy adopted the name “Oliver Norvell Hardy”—a name which he would occasionally mention in full throughout various Laurel and Hardy performances. Additionally, Hardy also received the nickname of “Babe,” as his Italian barber would apply talcum powder to his face, saying, “nice-a baby.” The nickname would briefly follow him into his early film career, with him occasionally also being credited as “Babe Hardy.”

Hardy entered show business as a singer, often performing at his local cinema. When yet another cinema opened near his hometown, he became interested in theater operations and worked as a janitor, manager, projectionist, and in the ticket booth. Soon enough, he was entranced by the actors he saw on screen and decided that he could be just as adept in his own performances. One of his friends encouraged him to go to Jacksonville, Florida, where he began working at the Lubin Manufacturing Company.

At the Lubin studio, Hardy was typically cast in villainous and “heavy” roles. Hardy was 6’1” and roughly 300 pounds, so the parts he received were limited by his stature. However, his physique worked well in comedies, providing a foil to his co-stars. After making roughly 50 films for Lubin, Hardy moved to New York and also filmed at Pathé, Casino, and Edison Studios, followed by a move back to Jacksonville to work at Vim Comedy Company.

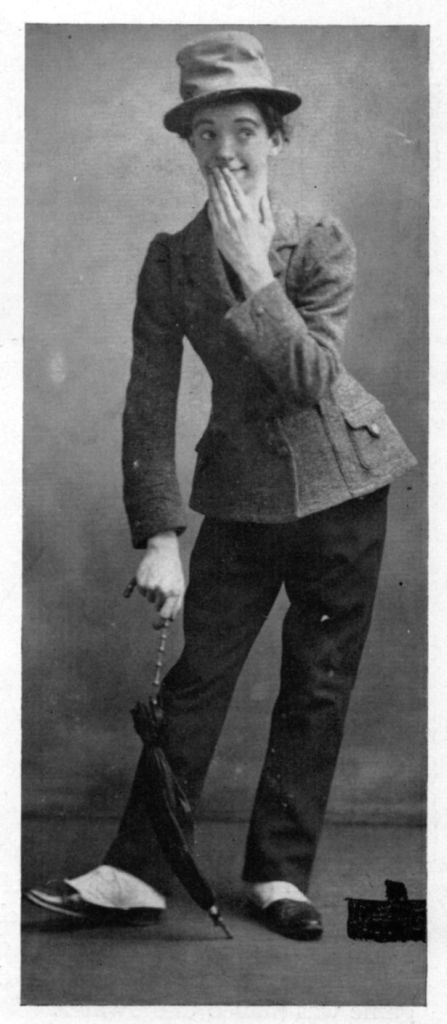

Later, Hardy moved across the country to Los Angeles and found freelance work in the film industry, making over 40 films for Vitagraph. It was at this point that Hardy first collaborated with British actor, Laurel. The two appeared in The Lucky Dog (1921), with Hardy’s character trying to rob Stan. They would not work together again on screen for another six years. In the meantime, Hardy worked for Hal Roach Studios, and can be noticed in Our Gang shorts and Charley Chase films. Additionally, he played the Tin Man in The Wizard of Oz (1925), followed with being directed by Stan in Yes, Yes, Yes, Nanette! (1925).

In 1927, Laurel and Hardy teamed up once more, leading to the production of several short films starring the duo. Two years later, they would appear in Hollywood Revue of 1929. Additionally, the duo starred in their first feature film, Pardon Us (1931), while still working on various short films. In fact, their short The Music Box (1932) won them an Academy Award for best short film. Upon the completion of Saps at Sea (1940), Laurel and Hardy left Hal Roach studios in order to perform for the USO during World War II. When they returned, they found work at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayor studios as well as 20th Century Fox. Laurel and Hardy would make their last film, Atoll K (1951), while also making time for occasional television appearances.

Laurel and Hardy’s collaborations spanned from the silent era and well into the transition to sound. Altogether, the comedic duo made roughly 106 films between 1921 and 1951, offering performance sin 34 silent shorts, 45 sound shorts, and 27 full-length feature films.

Unfortunately, Hardy suffered a heart attack in 1954 after making his way through rapid weight loss. Another stroke in 1956 affected his voice and mobility. Hardy died at age 65 on August 7, 1957.

Laurel did not make film appearances without his comedic partner. Nonetheless, he continued to write Laurel and Hardy material and also enjoyed responding to fan letters. His happened to be one of the few celebrity numbers publicly available in the phone book. He passed away on February 23, 1965.

Today, the legacy of Laurel and Hardy is celebrated by fans all over the world.

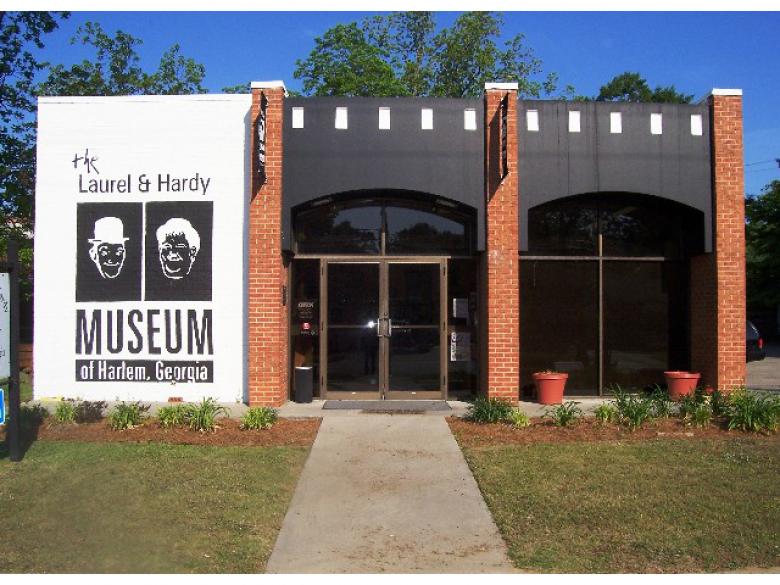

Although Hardy is one-half of a legendary comedy team, many residents of Harlem, Georgia, are extremely proud of their native son. In addition to historical makers pertaining to Hardy in Milledgeville and Harlem, Georgia, the Laurel and Hardy Museum also exists in Harlem.

Since its opening on July 15, 2000, visitors from all over the world have come to the Laurel and Hardy Museum in Harlem. In fact, on the first Saturday in October, the town holds the Oliver Hardy Festival, which draws a crowd well over the size of Harlem’s population. However, when it is time for business as usual, this museum is all but forgotten; travelers come and go, and locals drop in for a visit. After school, children stop by for homemade cookies and watch a short or two.

The museum itself exists due to a heartening responsibility of sharing and preserving the works of Laurel and Hardy. Moreover, its inception was highly influenced by Laurel and Hardy fans. In its infancy, the museum was no museum at all. Rather, people from all over the world would send Laurel and Hardy memorabilia to Harlem. Artifacts of all shapes and sizes were placed on display in City Hall, until there was simply no room left. As a result, through the collaboration of Laurel and Hardy fans, the community of Harlem, and a Mayor of Harlem who was incidentally related to Hardy, Harlem’s Laurel and Hardy Museum was born.

In addition to being a hub for the community, the museum houses an impressive collection of Laurel and Hardy’s works. The museum’s staff will gladly play any film or short for visitors in their theater area. Also, visitors can enjoy viewing the wide array of Laurel and Hardy memorabilia and artifacts, including photos, decorative collectibles, posters, lobby cards, and props, such as a fez from Sons of the Desert (1933). Moreover, the Laurel and Hardy Museum in Harlem is just one wonderful half of preserving the legacy of Laurel and Hardy; the sister museum operates in Ulverston, England, hometown of Laurel.

Outside of the Museum, one can take a short walk and find a plaque marking the spot where Hardy was born– just across the street from Ollie’s Laundry. Additionally, the town’s water tower features a towering caricature of Hardy’s face.

In England, Laurel’s birthplace is marked with a plaque. A statue of Laurel exists in Bishop Auckland on the site where his parents’ theatre once stood. Additionally, there is a statue of both Laurel and Hardy outside of Coronation Hall in Ulverston. There is also a plaque on the Bull Inn in Leicestershire, which marks the duo appearing in Nottingham in the winter of 1952.

While not in the hometown of either Laurel and Hardy, another location to which fans have made many a pilgrimage is the site of the Music Box steps in the Silver Lake district of Los Angeles. The stairs remain and are marked with a plaque and tribute street sign. They are located near Laurel and Hardy Park. Moreover, Silver Lake hosts an annual Music Box Steps Celebration in honor of the duo.

Overall, Laurel and Hardy continue to entertain classic comedy fans to this day. Their comedy is truly timeless and continues to connect with film fans all over the world.

Update 2021: The Laurel and Hardy Museum has since relocated to 135 N Louisville St, Harlem, GA 30814, inside of the Columbia Theatre building.