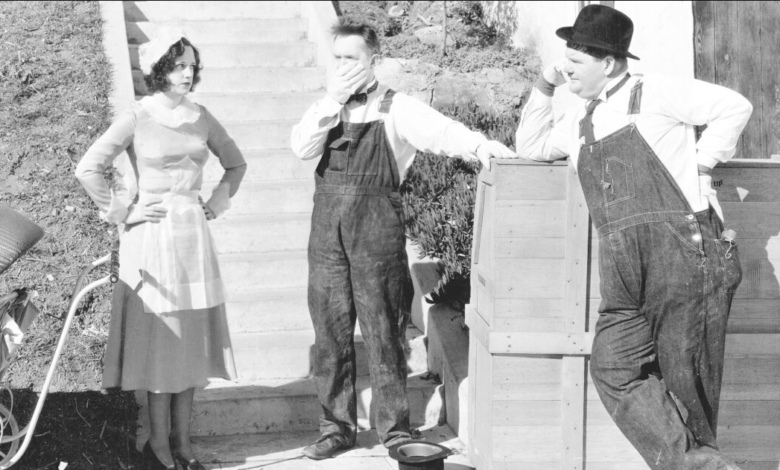

Stairway to Heaven. Laurel and Hardy in “The Music Box” (1932).

No Laurel and Hardy fan or completist references The Music Box as their favorite Stan and Ollie movie.

Citing this most famous of films as your personal favorite is a waste of an opportunity to show off your own wide-ranging knowledge. It’s like saying that Mozart is your favorite classical composer or that the Mona Lisa is your favorite painting. It’s just not a stated preference that confers what Adorno would call cultural capital and what Bourdieu would call “distinction”.

In all honesty, The Music Box isn’t the Laurel and Hardy film I most look forward to rewatching, despite (or perhaps snootily because) of its Oscar glory. Big Business, Helpmates, Towed in a Hole, Busy Bodies, and even Come Clean come higher on my top ten list, a list that’s always being revised.

You probably already knew that The Music Box was a remake of one of their own silent films (now lost) called Hats Off, in which our heroes heave a washing machine rather than a piano up this very same set of steps.

Our heroes have a delivery business – “Foundered in 1931”. This morning they are to deliver a piano (actually pianola) to the home of a snooty professor, as played by Billy Gilbert – one of the more colourful and melodramatic of recurring antagonists. The huge flight of steps does not deter them and with a contrapuntal heave and a ho they get that crate up the stairs despite many setbacks. LA Police officers in the 1930s were free to deal out discretionary nuggets of corporeal correction without fear of disciplinary action. At least they didn’t seem to kill people. Those who are momentarily inconvenienced by the slow ascent of this box are utterly without compassion for Stan and Ollie, and are unwilling to make the smallest concession to the notion of wriggling around. Each time the box is sent plummeting down to street level, Stan and Ollie sigh and resume their work uncomplainingly. Perhaps the best moment in the film is when Charley Hall informs them, having reached the front door, that the road where their cart is parked spirals round to the front door, making the whole laborious ascent redundant. There is nothing for it, but to slowly carry the box all the way down the steps so that this more logical strategy be belatedly effected.

The film is far from over with the ascent, however. Everything that can go wrong with a block and tackle goes wrong. Ollie suffers an agonising foot injury. Despite all the crashes the box has received, the pianola turns out to be in perfect condition, and we’re treated to a deliciously little dance number as they commence the clean up operation.

The conclusion to the film somewhat arbitrary. Gilbert attempts to destroy his own birthday present with an axe, becomes reconciled with his wife, and then has ink squirted in his face.

What is it that elevates this film to such canonical status? I’m inclined to think that it’s the steps themselves. Everybody has to carry something large and heavy up too many steps at some point in their lives. There’s nobody who can’t empathise with their condition. There’s an eerie beauty to these steps in any case. These steps belong in a pantheon of cinematic steps which include Eisenstein’s Odessa steps and the fatal steps in The Exorcist. Although I’m also reminded of A Matter of Life and Death, I am reminded that that film is dominated by an escalator, not a staircase.

I think I have an old blog somewhere about steps on film.