‘Shameful for America’: Two Latino Vietnam veterans fight deportation

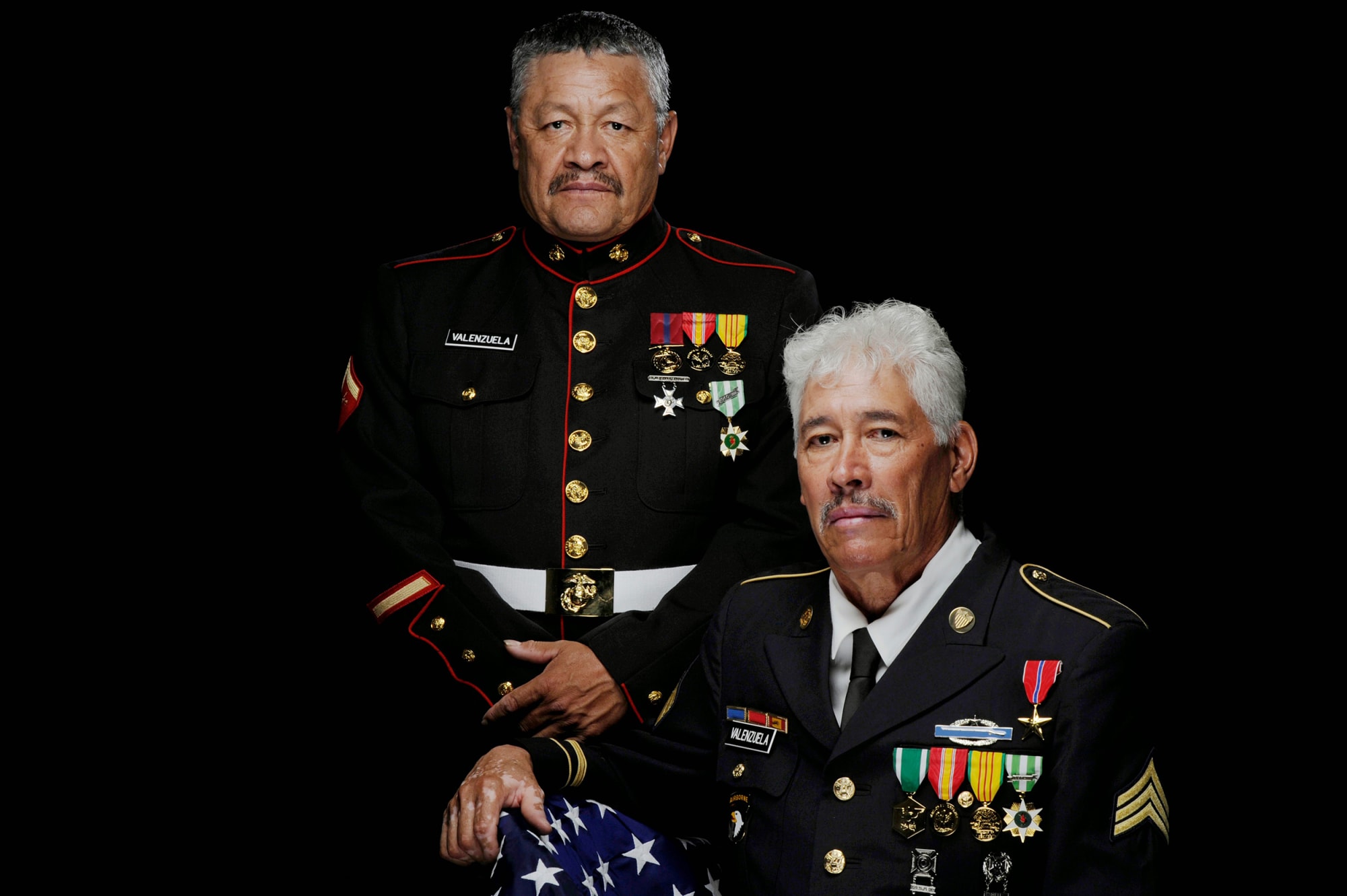

The PBS documentary "American Exile" follows two brothers — both Vietnam veterans in their 70s — as they fight to stay in the only country they have ever known.

During the Vietnam 𝕎𝕒𝕣, one of Valente Valenzuela’s grim tasks in the Army was collecting body parts from the battlefield, and then taking them to the dump. The young soldier experienced unimaginable horrors during his tour of duty. Once, to save his own life, he was forced to decapitate a violent terror suspect.

Valenzuela describes this ordeal as well as the one that would alter the course of his and his brother’s life decades after the 𝕎𝕒𝕣 in Vietnam ended in a new documentary, “American Exile,” which explores the plight of deported veterans and their families.

In 2009, Valenzuela and his brother Manuel, a Marine Corps veteran who also saw combat in Vietnam, received notices that the U.S. government was moving to deport them.

Airing Tuesday on PBS, the film follows the Valenzuela brothers — now both in their 70s — as they fight to stay in the only country they have ever known. Valente goes into exile in Mexico, while Manuel becomes an activist and takes their cause all the way to the White House.

Receiving a deportation notice was overwhelming for Valente. “There’s no word for how we feel. The last thing we think when we go to bed is we’re in removal notice. And the first thing when we wake up, is we’re in removal notice.” In the film, he calls their situation, and that of similar veterans, “shameful for America.”

About 65,000 foreign nationals, mostly green card holders, serve in the U.S. military at any given time, the film notes. “For most of U.S. history, we never deported veterans, although foreign nationals have been serving in the military since the Revolutionary 𝕎𝕒𝕣,” said “American Exile” director John J. Valadez. “Veterans always had a special status.”

Valadez sees the Valenzuela brothers’ saga as “a story of hope” that shows how individuals can effect change. It is a story not without its dark points, however; viewers see Valente toss his medals into the Rio Grande in frustration.

Manuel, who travels the country raising awareness for deported veterans, said that everyone he encounters is shocked by what is happening. “To this day, most people don’t know that the U.S. deports veterans. People always ask me, ‘Are we really doing this?’”

Until recently, the answer was “yes.”

The genesis of the Valenzuela brothers’ immigration troubles goes back to 1996 when then-President Bill Clinton signed the Illegal Immigration Reform and Responsibility Act. “This law made more crimes, including relatively minor ones like shoplifting and possession of marijuana, grounds for deportation,” said attorney Mariela Sagastume. “It took away judges’ discretion to consider military service, community ties, family ties and other mitigating factors in deportation cases. It was also retroactive, meaning that someone could be ordered out of the country for crimes they had literally committed decades ago.”

That’s what happened to the Valenzuela brothers.

When they initially returned from Vietnam, readjusting to civilian life proved difficult. Valente pled guilty to several misdemeanors, including assault and theft. Manuel’s misdemeanors included battery and resisting arrest. Both brothers were later diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder and classified as disabled. Still, over the years they were able to rebuild their lives and live with stability — until they received the orders of removal for the acts they committed as young men.

Sagastume said that it is a misconception that serving in the U.S. military automatically confers citizenship. “Very often, service members are assured that all of their citizenship paperwork will be taken care of (by the government).” In fact, noncitizen veterans must still go through the naturalization process.

Along with other lawyers and nonprofit groups, Sagastume has represented the Valenzuela brothers pro bono. She has worked on other deported veteran’s cases, such as that of Hector Barajas-Varela, a veteran who was able to return home in 2016 after receiving a pardon from California’s governor.

“They were discarded”

There is no official tally of the number of veterans that the U.S. government has deported, because immigration authorities do not keep statistics on military service of deportees. Most deported veterans are sent to Mexico, although some have been sent to Jamaica, South Korea, the Philippines and Nigeria.