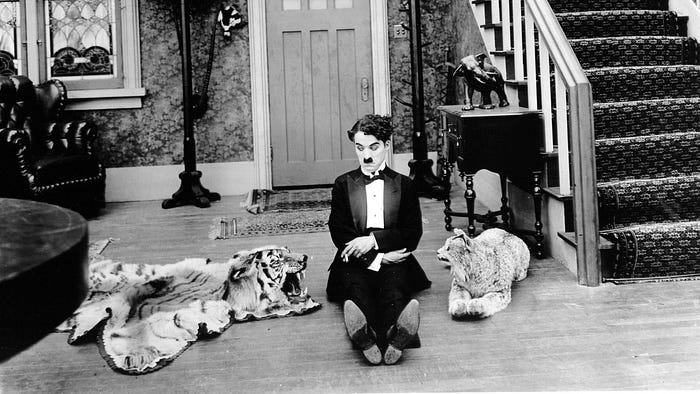

The Immigrant Is Chaplin’s Most Famous Short for a Reason

Note: This is the ninety-first in a series of historical/critical essays examining the best in film from each year. Essentially, I am watching films from the beginning of cinematic history that interest me and/or hold some critical or cultural impact. My personal, living list of favorites is being created at Mubi, showcasing five films per year. All this being explained, what follows is an examination of my favorite 1917 film, THE IMMIGRANT, directed by Charlie Chaplin.

THE IMMIGRANT was Charlie Chaplin’s penultimate film for Mutual, the only studio he had thus far been with for more than a year. But the second year of that partnership, which would be its last, saw a critical change in how Chaplin approached filmmaking. He only made four movies in 1917, by far the fewest he had turned out since he entered the motion picture business in 1914. Those four (EASY STREET, THE CURE, THE ADVENTURER, and, of course, THE IMMIGRANT) are often considered among his best shorts. You see, Chaplin was testing Mutual’s patience and money. He was the highest paid film star in the world, and he knew it, and he used this power to focus on quality, not quantity…although I would be hard pressed to say even the worst products of his high-volume Keystone year were of low quality.

Still, Chaplin was seeking new highs for film comedy. And he found it in THE IMMIGRANT, certainly among his best shorts, if not his second best (we’ll get to the first with 1918). It nearly occupies this distinction with another Mutual short, ONE A.M. (1916), but the two are nearly polar opposites in their approach, although they are united by a singular, unique vision to comedy filmmaking for the time. ONE A.M. was a pure gag, singularly driven by Chaplin in an essentially solo performance across a 25-minute long film. THE IMMIGRANT is a story of human interaction, and one with a lot to say about America, class, and immigration.

As illuminated by Kevin Brownlow and David Gill’s documentary series UNKNOWN CHAPLIN (1983), the very thing THE IMMIGRANT is known for (namely, the immigrant part) wasn’t part of the initial genesis for the film. Chaplin’s first idea was to simply place a man who had never been in a restaurant before into, well, a restaurant. Hilarity ensues. But when considering why a man who had never been in a restaurant before would now be in a restaurant (a possibility for an immigrant in 1917, I guess), Chaplin crafted the whole first part of the short, and reworked the concept to have the Tramp “simply” penniless. This is the kind of thing you have to imagine Mutual’s lax hand (whether they wanted it to be lax or not) facilitated. Certainly, Chaplin’s ambition flourished throughout his time there.

But as mentioned, THE IMMIGRANT is today remembered mostly for its first half, before Chaplin’s immigrant Tramp makes his way into giant head waiter Eric Campbell’s restaurant. On a boat from an unspecified country, Chaplin’s character plays cards, eats in the constantly tilting mess hall (accomplished with a set on rollers), and meets Edna Purviance’s character, played to perfection by the star’s leading lady. Purviance portrays a sympathetic and charming woman who ends up helping Chaplin as much as he helps her. After Purviance’s immigrant and her mother are robbed, the Tramp puts some of his gambling winnings into the pocket of Purviance…but not all of it, in a brilliant exchange that illustrates the dichotomy of the rascally Tramp and the kind-hearted Tramp. The former is even what led to the gambling winnings in the first place! But when he’s accused of being a pickpocket, Purviance clears his name.

In a genuinely sobering and beautiful moment, the group of immigrants stare wonderingly at a fantastic shot of the Statue of Liberty…before being roped off by a worker like cattle. This is probably THE IMMIGRANT’s most famous scene, as the parallels being drawn and commentary being, uh, commented aren’t hard to understand. Chaplin’s Tramp even kicks an immigration agent in the butt! Somehow, this scene apparently played a part in proving Chaplin’s anti-Americanism when he was “exiled” from the United States in 1952.

But even at the time of release, Chaplin was coming under fire for a perceived lack of patriotism…but apparently not from Americans. Never formally an American citizen but always a British one, Chaplin was criticized for not fighting in World War I. He “made himself available” to Britain, the government of which believed he was of greater value as a propaganda tool, and was even registered for the American draft. The United States government probably felt similarly. This kind of pointed attention was a result, of course, of Chaplin’s superstar presence, which had manifested in merchandise, impersonators in film, and recreations in ordinary society. Apparently, nine out of ten men who attended costume parties dressed as the Tramp (per David Robinson’s biography CHAPLIN: HIS LIFE AND ART [1985]). This kind of celebrity worship would likely warp the mind of the comic genius, leading to some more than questionable personal decisions just as his career was soaring financially and developing critically…but we’ll get to that in a later essay.

In any event, in THE IMMIGRANT, Chaplin’s Tramp and Purviance’s immigrant are separated, but they run into each other once again in the restaurant that served as the film’s initial focus. Before this, though, the poverty-stricken Tramp had found a coin on the street. He didn’t notice, however, that it fell right out of a hole in his pocket. The Tramp learns that the mother of Purviance’s immigrant has since died, and Campbell’s reliably hulking villain, the head waiter, finds frustration in the Tramp’s restaurant etiquette. This is probably a good time to mention that, as much attention as the film gets for its “deeper” themes, THE IMMIGRANT is also just tremendously funny.

From the rolling boat to Chaplin’s mannerisms at the card table to his entire exchange with Campbell and Purviance in the restaurant, the sheer joy of the performances and gags is palpable. But then, it only makes the poignant moments all the more impactful, such as when an artist saves the Tramp from “certain death” (a coin Chaplin had presented Campbell’s waiter, retrieved by slick and hilarious means, ended up being fake). The artist, played by mainstay Henry Bergman, offers to pay for the couple’s meal, which the Tramp kindly declines just a few times…but he’s shocked when the artist takes him up on the refusal.

The Tramp’s tricks and ingenuity, as well as the (oft-overused term of) pathos that Chaplin employs in strengthening the movie’s laughs, make for an incredible blend of emotions. You can’t have the good without the bad, and while THE IMMIGRANT doesn’t get truly morbid by any means, the misfortunes of its characters are not lost on the audience. This is a truly honest, sympathetic tale of making it in a country not truly kind to outsiders, and it’s funny to boot. And it’s both relevant and amusing 111 years later. If you watch one short from before Chaplin’s full-fledged feature filmmaking career, let it be A DOG’S LIFE (1918), but then watch THE IMMIGRANT anyways!